Why your metabolic health determines how fast your brain ages

For decades, cognitive decline was viewed primarily as a neurological problem. Today, high-quality human trials, genetic research, and vascular biology have made one fact clear: the brain ages according to the health of the body. Hypertension, insulin resistance, and elevated ApoB are not only cardiovascular risks, they directly damage the brain’s vasculature, accelerate cognitive aging, and increase the likelihood of dementia.

Modern neuroscience now considers metabolic health a central pillar of brain longevity. The mechanisms are not theoretical; they are well established and measurable in clinical research.

Metabolic Health and the Brain: Causality, Not Correlation

Large trials in humans show that improving metabolic markers translates into measurable cognitive benefits within just a few years. When blood pressure is tightly controlled, or when atherogenic lipids such as ApoB are lowered, the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia decreases. These findings demonstrate causality: improving metabolic health actively slows brain aging.

Genetic studies reinforce this relationship. Mendelian randomization shows that lifelong exposure to higher metabolic risk (such as elevated LDL or insulin resistance) increases the probability of cognitive decline. This means the relationship is not just associated; it is biologically linked.

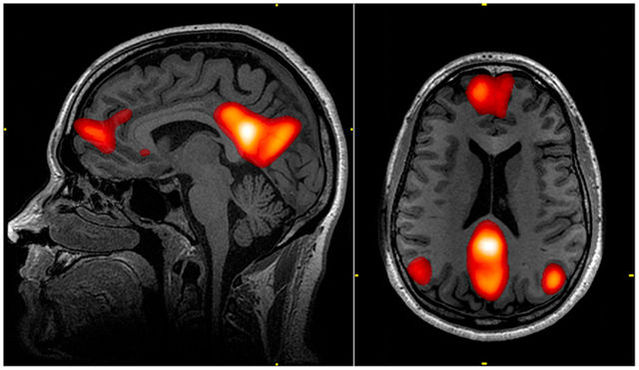

The underlying biology is well understood. The brain depends on a dense network of tiny blood vessels, and anything that injures vascular or endothelial tissue can impair cognition. High blood pressure damages the small vessels supplying the brain. Elevated ApoB contributes to atherosclerosis and compromises blood flow. Insulin resistance increases glycation, inflammation, oxidative stress, and disrupts capillary function. Together, these mechanisms create an environment where neurons receive less oxygen and fewer nutrients, while being exposed to more inflammation and oxidative damage. Over years, this accelerates cognitive decline.

The Three Core Levers of Brain Metabolic Health

Although many factors influence cognitive aging, three stand out as the most powerful and consistently supported by evidence: blood pressure, ApoB, and insulin sensitivity. These markers determine the health of the blood vessels that supply the brain and the metabolic environment in which neurons must function.

Blood pressure is critical because the brain’s microvasculature is extremely sensitive to pressure-related injury. Sustained hypertension damages the delicate vessels that keep brain tissue nourished. Keeping blood pressure within a healthy range — typically around the 120/80 mmHg range, according to major medical guidelines — helps preserve the structural integrity of these vessels and supports long-term cognitive stability.

ApoB, which represents the number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles, is directly involved in the development of plaque within blood vessels, including those that supply the brain. Lowering ApoB reduces vascular damage and improves long-term brain health. This is one of the clearest examples of cardiovascular and neurological health intersecting: what protects the heart also protects the brain.

Insulin sensitivity is equally important. When the body becomes resistant to insulin, blood glucose rises and produces a cascade of biological stressors — including inflammation, glycation, mitochondrial strain, and oxidative stress — all of which are harmful to neurons. Improving insulin sensitivity through lifestyle interventions such as exercise, adequate protein intake, fiber-rich meals, and consistent sleep helps stabilize blood sugar and supports metabolic conditions that are more favorable for the brain.

When these three levers improve together, brain aging slows. This is one of the most reproducible findings in modern longevity science.

Why Some People Are at Higher Risk

Genetics can modify the impact of metabolic health on brain aging. For example, individuals who carry the APOE-ε4 allele, a well-known genetic variant associated with Alzheimer’s disease, are more sensitive to metabolic insults. When metabolic dysfunction such as diabetes or elevated ApoB is present alongside APOE-ε4, the risk of cognitive decline increases more than either factor alone. This does not mean that cognitive decline is inevitable; rather, it means that metabolic optimization is even more important for these individuals.

These risks rarely occur in isolation. High blood pressure, elevated lipids, and high glucose tend to cluster, especially in people with poor metabolic fitness. This makes lifestyle intervention essential.

Across all levels of genetic risk, exercise remains one of the most powerful tools for improving metabolic function. Aerobic training enhances mitochondrial efficiency and cardiovascular capacity. Resistance training improves insulin sensitivity and increases muscle mass, which helps regulate glucose. Together, these adaptations support a metabolic profile that protects the brain over time.

Genes set the baseline, but habits shape the trajectory.

Taking Action: Supporting Metabolic and Cognitive Health

Protecting the brain begins with understanding your metabolic profile. This starts with simple measurements such as home blood pressure readings and basic blood tests for lipids, fasting glucose, and HbA1c. These markers offer a clear picture of how your metabolism is aging and how much support your brain may need.

Improving metabolic health requires consistency rather than complexity. Regular aerobic exercise, ideally complemented by intervals that challenge cardiovascular capacity, strengthens the systems that supply the brain. Strength training further enhances metabolic regulation. Nutrition that emphasizes fiber, adequate protein, and balanced glucose responses, paired with a stable sleep routine, creates a metabolic environment that supports long-term cognitive resilience.

Every improvement you make in metabolic health is an investment in brain health.