We Evolved as Ultra-Social Organisms

Human biology was shaped in an environment where isolation simply didn’t exist.

For nearly all of evolutionary history, our ancestors lived in small cooperative groups, sharing resources, protection, and constant physical proximity.

Safety, sleep, food, and survival were all interdependent.

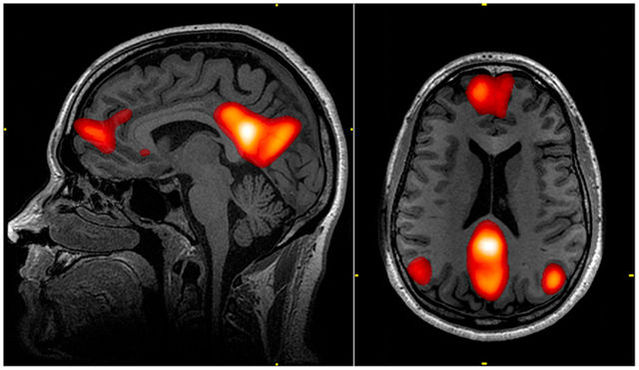

Because of this, our stress response, immune signaling, and reward circuitry developed under one assumption: Connection is the default state.

When the brain senses social isolation, even subtle forms, it activates threat responses designed for emergency conditions:

higher cortisol, increased inflammatory tone, reduced parasympathetic activity, impaired sleep architecture, and a shift toward survival-based behaviors.

From a biological perspective, isolation is danger.

Connection is safety.

The Experiment That Changed How We Think About Behavior

A landmark experiment, often referred to as Rat Park, illustrated this in a powerful way, not because rats mimic humans, but because the underlying biology is conserved across mammals.

Researchers placed rats alone in small, empty cages.

They had access to two bottles: plain water and drug-infused water (morphine).

Isolated rats repeatedly chose the drug solution, often to the point of severe health decline or death.

Their biology, deprived of connection and stimulation, pushed them toward compulsive, self-destructive behavior.

What Happened When They Added Community

In a second phase, researchers recreated the setup, but this time housed rats in a large, enriched environment with other rats, physical space, toys, and constant social interaction.

The results reversed: