Health is a brain adaptation

Most people think becoming healthier is simply about motivation or discipline. But modern neuroscience shows a different picture: health is fundamentally a brain adaptation. Our habits, our patterns of self-talk, our expectations, and the way we respond to discomfort are all built into neural circuits that can either support change or silently sabotage it.

Improving your health is not about willpower.

It’s about rewiring the brain to make difficult things feel possible, normal, and eventually automatic.

This article breaks down the science behind why certain habits feel hard, why identity matters, and how deliberate, consistent action reshapes the nervous system.

How Thoughts Become Neural Pathways

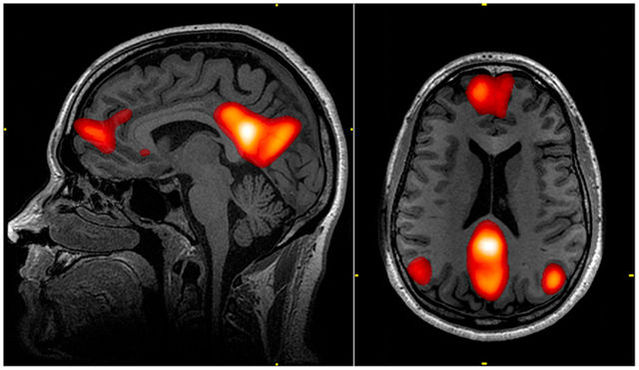

The brain continuously learns through neuroplasticity — the process through which neural circuits strengthen with repetition. Thoughts, emotions, and behaviors all leave biological traces in the brain. When a thought is repeated often enough, the neurons involved fire together more easily, and over time this pathway becomes the brain’s “default setting.”

This is why self-talk matters.

A repeated internal narrative like “I can’t do this” becomes a practiced neural pattern the brain executes automatically.

Likewise, shifting the internal script to “I’m someone who moves daily” begins forming a new pathway — but only when paired with consistent action.

Neuroscience shows that thought + action + repetition is what stabilizes a new behavior at the neural level. This is how habits transition from effortful to automatic. You are not changing your personality — you are changing the underlying circuitry.

Mindset, Expectations, and the Brain’s Predictive Model

One of the most replicated findings in neuroscience and medicine is the placebo–nocebo effect, which has nothing to do with imagination and everything to do with how the brain predicts outcomes.

Expectations shape perception, pain, symptoms, and motivation.

If someone anticipates failure or discomfort, the brain filters for signals that confirm those expectations. This leads to increased pain perception, reduced effort, poorer performance, and more withdrawal when things feel hard.

The opposite is also true.

When the underlying identity shifts toward growth — “I’m becoming someone who trains regularly” — the brain begins to allocate attention, motivation, and energy toward behaviors that match that identity. This shift produces measurable improvements in health outcomes, because neural pathways controlling effort, reward, and regulation start firing in alignment with the new expectation.

You don’t behave your way into a new identity.

You wire your way into it.

Why Healthy Habits Feel Hard Before They Feel Easy

The brain is metabolically expensive: it uses about 20% of the body’s energy. From an evolutionary standpoint, the brain was designed to conserve energy, not expend it. This means anything unfamiliar or effortful — exercise, new routines, hard conversations, disciplined choices — is initially interpreted as a potential threat or unnecessary expenditure.

The discomfort you feel when starting a new habit is not weakness.

It is your nervous system trying to protect you.

If you quit when it becomes uncomfortable, the brain learns retreat.

If you push through the initial discomfort, the brain adapts and integrates the behavior more efficiently.

Repeated exposure to challenge triggers adaptation in circuits involving the anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex — the regions responsible for effort, emotion, and regulation. Over time, the reaction changes from “this is a threat” to “this is normal.”

This is the biological basis of toughness, resilience, and habit formation.

“I could never” eventually becomes “this is who I am.”

Identity, Effort, and Long-Term Health Behavior

Neuroscience shows that behavior change is most stable when tied to a shift in self-identity, not temporary motivation. This is because the brain makes predictions about the world through “priors” — internal models built from experience. If your identity says you are someone who avoids effort or quits under discomfort, the brain aligns behavior with that model.

But when identity evolves — even slightly — the brain begins to update those priors.

“I walk every day.”

“I’m someone who values exercise.”

“I take care of my metabolic health.”

As identity changes, behavior becomes easier because it now matches the brain’s internal map.

This is the neuroscience behind “you vs. you”:

The real battle is not between your present and future self — it is between two neural circuits competing for dominance.

The Brain Learns by Doing: Why Action Matters More Than Motivation

Motivation is a feeling; action is a signal to the nervous system.

Every time you act — even if the action is small — the brain receives evidence that the new pathway is relevant and worth reinforcing.

The dorsal striatum, a key structure in habit formation, becomes active only through consistent behavior. This is why starting is often the hardest part: the brain cannot automate what has not been repeatedly practiced.

Small, consistent actions are not psychologically comforting; they are biologically necessary for habit formation.

Neural pathways strengthen through:

• consistency

• repetition

• emotional coherence (why it matters)

• identity alignment

• experiences that challenge and expand capacity

This is how effort turns into ease.

Becoming Healthier Is a Brain Process, Not a Personality Trait

Health is not built from perfect discipline.

It is built from understanding how the brain adapts:

• Pathways become habits

• Expectations shape physiology

• Discomfort precedes adaptation

• Consistency rewires reward systems

• Identity determines the path of least resistance

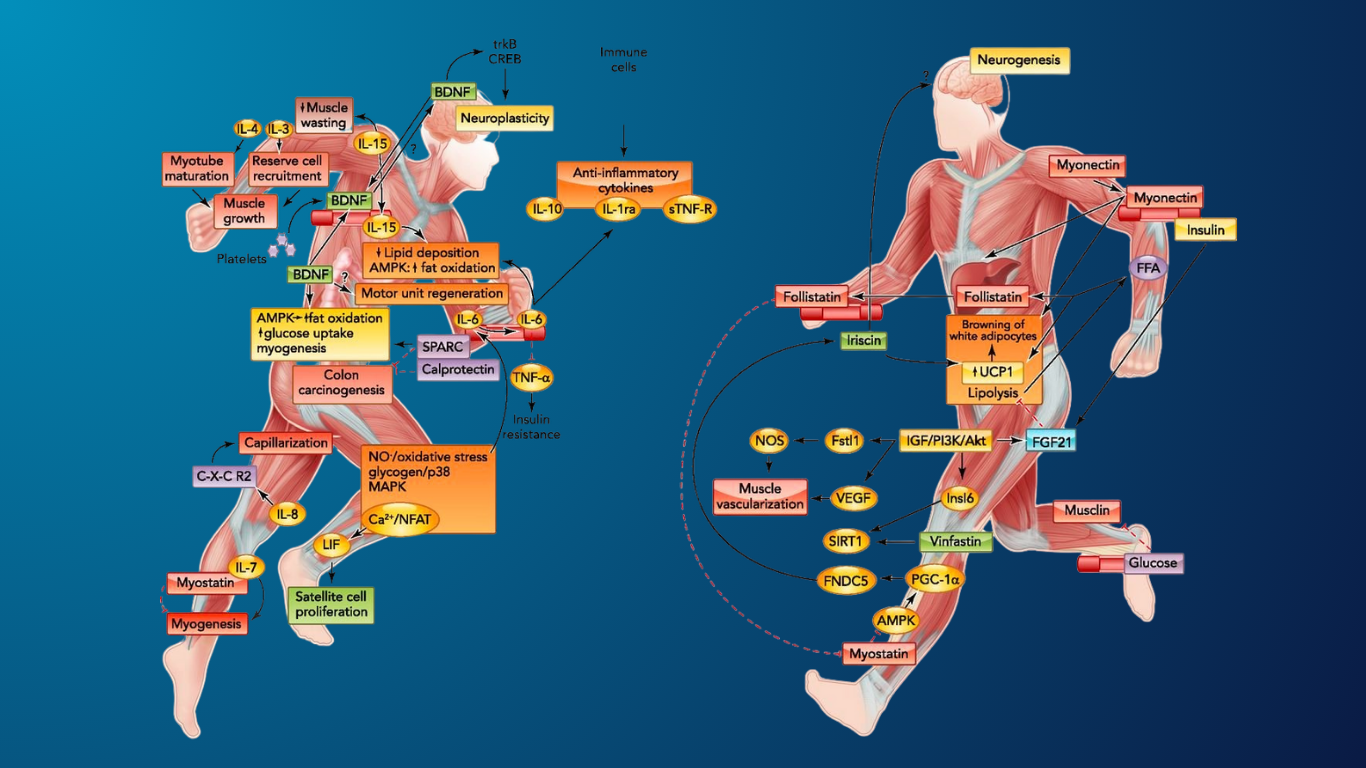

Becoming healthier is fundamentally a process of modifying neural circuits related to effort, reward, and regulation. When these pathways adapt through consistent behavior, the brain reduces the perceived cost of healthy actions and increases their automaticity. What once required deliberate effort becomes a stable, self-reinforcing pattern supported by the nervous system.